The World Luxury Council (India) recently hosted a vintage art exhibit at The Oberoi in Mumbai called Mumbai 100 Years Ago

On display were unpublished archival prints of some of the city's most prominent landmarks on canvas.

Dhara Patel, the business head of the World Luxury Council informed that these prints were sourced from a consortium of collectors.

|

| Mumbai 100 years ago |

"Some of these were postcards, others were photographs, which were bought from collectors, revived with special ink and printed on a special canvas that would guarantee them a life span for the next 100 years," she said.

Patel also said that while these prints could be reproduced on request, they would be restricted to only 10 prints of each picture.

The World Luxury Council is headquartered in London and deals in international business in the luxury arena. It provides assistance and advice to luxury brands by designing promotions and creating distribution and networking platforms.

Ticca Garis & taxis parked outside Taj Mahal Hotel (Year: 1885)

Ticca Garis were horse-drawn Victoria carriages (named after the British monarch), and were the only mode of transport to come to Bombay in 1882 after The Bombay Tramway Company Limited was formally set up in 1873.

The Bombay Presidency enacted the Bombay Tramways Act 1874, under which the company was licensed to run a tramway service drawn by one or two horses. In 1905, the newly formed concern, The Bombay Electric Supply & Tramways Company Limited, bought The Bombay Tramway Company, and the first electrically operated tram cars appeared on the city roads in 1907.

|

| Bombay |

There were three categories of Ticca Garis, or licensed cabs. Those of the first class were conspicuous by their absence and it was rumoured that the term was applied to funeral carriages. The second class Ticca was less stoutly constructed but cleaner than the London four-wheeled cab of that time. Ticcas belonging to the third class were ramshackle contraptions drawn by half-starved ponies.

This quaint mode of transport was gradually replaced in time. The first automobile was brought to Bombay in 1897-98. The first car imported by an Indian belonged to the eminent industrialist Jamshetji Tata. Motor taxis were introduced in 1811 whereas motorbuses started playing in 1926.

|

| Taj Hotel |

Today, the Victorias in front of the Taj have been replaced by black and yellow taxis. But, one can still hire a Ticca Gari for a negotiated sum and drive along the sea face for an experience.

Esplanade Road Kala Ghoda (Year: 1887)

Renamed Mahatma Gandhi Road, Esplanade Road, like most parts of South Bombay, is lined with heritage structures; Elphinstone College and the David Sassoon Library are amongst the prominent ones.

|

| Kala Ghoda |

Established in 1856, Elphinstone College is one of the oldest of colleges of the University of Bombay. It played an important role in the spread of Western education in the city. During the British Raj, the college was amongst the most coveted, producing several luminaries like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Pherozeshah Mehta, Jamshedji Tata, Homi K Bhabha and Dadabhai Naoroji. Inception classes of the University of Bombay were held here before being moved to the Fort campus.

The building was originally meant for the government central press; and although, the building is now a college, about half of the floor area is shared with the Maharashtra Archives Department.

The building, constructed in the 'Romanesque Transitional' style, cost Rs 750,000 to build. Sir Cowasjee Jehangir generously donated the amount. Today, it is categorised as a Grade I heritage structure.

|

| KD |

The well-known Jehangir Art Gallery is across the street as also the entrance to the Prince of Wales Museum (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya).

The David Sassoon Library was the brainchild of Albert Sassoon, son of the famous Baghdadi Jewish philanthropist, David Sassoon. Architects J Campbell and G E Gosling constructed it for the Scott McClelland and Company.

It cost Rs 125,000 to build, of which David Sassoon donated Rs 60,000; the government paid the remaining amount. Completed in 1870, the building was built using yellow Malad stone, much like the abutting Elphinstone College, Army and Navy Buildings and Watson's Hotel. A white stone bust of David Sassoon rests above the entrance portico

Rajabhai towers and Bombay University (Year: 1878)

Standing tall at 85 metres (280 feet), the Rajabai Tower was designed by English architect Sir George Gilbert Scott and modelled on the Big Ben in the UK. Premchand Roychand, a successful businessman who established the Bombay Stock Exchange, covered the cost of its construction on the condition that the clock tower be named after his mother Rajabai.

Roychand's mother was a devout Jain who ate her dinner before sunset. And, since she was blind, the evening bell of the tower helped her know the time of the day.

|

| Rajabhai Tower |

The foundation stone for the structure was laid on March 1, 1869. Construction was completed in November 1878 and cost Rs 2 lakh -- a handsome sum in those times.

A fusion of Venetian and Gothic styles of architecture, the tower was built using the locally available buff coloured Kurla stone. Its stained glass windows are still one of the best in the city.

In the times of the British Raj, one could hear the tower play 16 different tunes (including 'Rule Britannia', 'God Save the King' and 'Home! Sweet Home!'), which changed four times a day. Today, it chimes a single tune every 15 minutes.

The tower, the tallest structure in Bombay at one point, was closed to the public when it became a spot frequented by the suicidal.

|

| Rajabhai Tower Ground |

The campus of the University of Bombay (University of Mumbai as of September 1996) was established in 1857 in Fort. It was one of the first educational institutions founded by the British in India. Built in the Gothic style of architecture, it houses the administrative division of the university and a library that holds many original manuscripts. It has been given a five-star ranking by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC), and has a world ranking of 401.

Its long list of prominent alumni includes leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Lokmanya Tilak and BR Ambedkar as well as personalities like Shabana Azmi, Anant Pai, Mukesh Ambani, Anand Patwardhan and Aishwarya Rai.

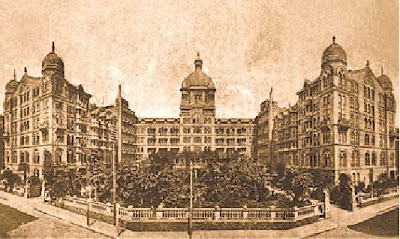

Bombay Municipal Corporation (Year: 1893)

The headquarters of India's richest municipal organisation is the Bombay Municipal Corporation or BMC Building. Renamed Brihanmumbai Mahanagar Palika, it is considered a Grade IIA heritage building and houses the civic body that governs the city of Mumbai.

It has a motto: 'Yato Dharmastato Jaya', which is Sanskrit for 'Where there is Righteousness, there shall be Victory' this is inscribed on the banner of its Coat of Arms.

|

| BMC Building |

The BMC was created in 1865 and Arthur Crawford was its first Municipal Commissioner. The municipality was initially housed in a modest building at the terminus of Girgaum Road.

In 1870, it was shifted to a building on the Esplanade, located between Watson Hotel and the Sassoon Mechanics Institute, which is where the present Army & Navy building is situated.

On December 9, 1884, the foundation stone for the new building of the Bombay Municipal Corporation was laid opposite Victoria Terminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus) by the then Viceroy, Lord Ripon.

|

| BMC |

Two designs were considered for the building -- a Gothic version by FW Stevens and an Indo-Saracenic version by Robert Fellowes Chisholm. The former was selected. And the imposing structure was completed in 1893, with its tallest tower rising up to 77.7 metres (255 feet).

The chief architectural feature is its central dome, which rises to a phenomenal height of 71.5 metres (234.6 feet) and is visible even from a distance. At the entrance stands an impressive bronze statue of Sir Pherozeshah Mehta, giving a picturesque view of the roads and buildings in front.

Victoria Terminus Railway station (Year 1887)

Victoria Terminus (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus) was the headquarters of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway and now of the Central Railway.

Architect Frederick William Stevens designed the station and received Rs 16.14 lakh for his work, a staggering amount for those days. Stevens earned the commission to construct the station after a masterpiece watercolour sketch by draughtsman Axel Haig.

|

| VT Station 1 |

Though rumours suggest that the design was originally designated for Flinders Street Station, there is no evidence in its favour. However, the final design is similar to the St Pancras railway station in London.

The station was named 'Victoria Terminus' in honour of the Queen and Empress Victoria, and was opened on the date of her Golden Jubilee: June 20, 1887. Built in the Gothic architectural style, with Wilsom Bell Mice as the chief engineer, the structure took 10 years to be completed.

|

| VT Station 2 |

The crowning glory is the central dome carrying at its apex, a colossal 5 metre (16.6 feet) high figure of a lady holding a flaming torch in her right hand and a wheel in her left hand that symbolises 'progress'. This dome is reportedly the first octagonal ribbed masonry dome that was adapted to an Italian Gothic style building. The interior of the dome is exposed to view from the ground floor, and the dome-well that carries the main staircase has been artistically decorated.

On the faade are also large bass-relief sculptures of 10 directors of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway Company, including Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy and Sir Jagannath Shankar Seth.

The entrance gates to Victoria Terminus carry two main gate columns, which are crowned, one with a Lion (representing the United Kingdom) and the other with a Tiger (representing India), both sculptured in Porbunder sandstone. In 1969, the statue of Progress was damaged due to lightning, but the Central Railway authorities with the help of Professor VV Manjrekar of the JJ School of Arts successfully restored it.

In 2004, the station was nominated as a World Heritage Site by the World Heritage Committee of UNESCO

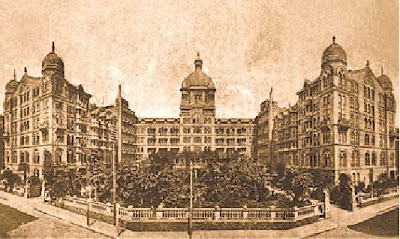

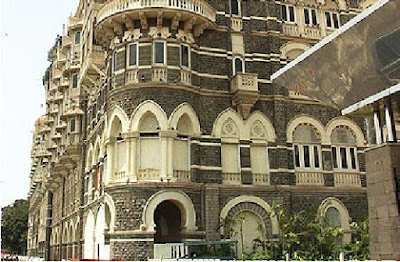

Taj Palace Hotel Entrance (Year: 1903)

The Taj Mahal Palace Hotel is one of the city's most iconic landmarks, and is located near the Gateway of India at Apollo Bunder.

Jamshedji Tata, a Parsi entrepreneur and prominent industrialist, commissioned this five-star luxury hotel. Built in the Indo-Saracenic architectural style and containing 565 rooms, the Taj Mahal Palace hotel resort opened its doors to its guest for the first time on December 16, 1903.

|

| Taj Hotel - Then |

Sher Singh was the old owner of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel; now it is a part of the Taj Hotels, Resorts and Palaces. During World War I, the hotel was converted into a 600-bed hospital.

Sitaram Khanderao Vaidya, Ashok Kumar and DN Mirza were the Indian architects on this project, which was completed by the English engineer WA Chambers. Khansaheb Sorabji Ruttonji Contractor was the builder, who also designed and built its famous central floating staircase.

To build the dome of the hotel, Jamshedji Tata imported the same steel that has been used in the Eiffel Tower. The hotel is the first in India to install and operate a steam elevator. The cost of construction totalled a massive 250,000.

|

| Taj Hotel - Now |

The side of the hotel seen from the harbour is actually its rear with the front facing away to the west. Rumour has it that the builder misread the architect's plans, but this is not true. The hotel was deliberately built facing inland as it provided an easier approach for the horse carriages of those days. Today, the old front has been closed and access to the hotel is from the harbour side.

According misconception about the Taj is that Jamshedji Tata decided to build this luxury hotel because he was denied entry into the 'whites only' Watson's Hotel. This claim has been challenged by some commentators who say that Tata was unlikely to have been concerned with revenge against his British adversaries. They believe that it was the editor of the Times of India who urged Tata to build a hotel "worthy of Bombay".

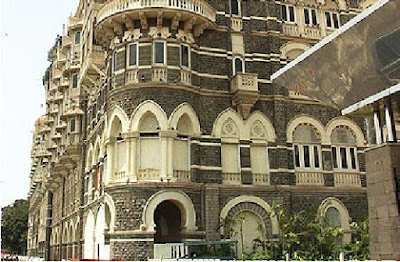

Hotel Majestic and Waterloo Mansion (Year 1890)

Situated a few minutes away from the business district of Ballard Estate and the art area of Kala Ghoda, the Majestic Hotel was one of the city's best hotels, offering its clients a variety of dining and other facilities.

WA Chambers designed it in the Indo-Saracenic architectural style. Chambers was also the engineer on the famous Taj Mahal Palace Hotel at Apollo Bunder.

|

| Hotel Majestic - Then |

Along with the Waterloo Mansion next door, the Majestic Hotel became one of the most photographed pieces of architecture in the city and was frequently featured in postcards of the early 20th century.

Unfortunately, post Independence, like it has been with many of our heritage sites, the condition of the building deteriorated due to lack of interest in preservation. The government eventually took over the property in the 1960s and renamed it Sahakari Bhandar. Now, it has been completely transformed and performs the dual function of a cooperative general store and a hostel for members of the legislative assembly.

|

| Hotel Majestic - Now |

The erstwhile Waterloo Mansion, which was then built exclusively for residential purposes, is now referred to as the Indian Mercantile Building. Its architectural style is Gothic with turrets, pointed arches and black stone faades. Old postcard pictures depict each tower being topped with a red tiled pyramidal roof. It is not known when and why these roof structures were removed.

Both, the Majestic Hotel and the Waterloo Mansion, are located near the Wellington Fountain Circle, also known as the Regal Circle, but officially renamed as Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Chowk

Pydownie Mohammed Ali Road (Year unknown)

Mohammed Ali Road is a stretch between the junctions of Crawford Market and Mandvi Post Office. This vital artery of the city's road network is named after the late freedom fighters, Maulana Mohammed Ali and Shaukhat Ali.

|

| Mohammed Ali Road - Then |

The brothers had joined hands with Mahatma Gandhi to launch the Khilafat Movement against the British. After the First War of Independence in 1857, this was the first major instance of Hindu-Muslim unity. Maulana Mohammad Ali was also one of the founders of the Jamia Millia Islamia (Central University), New Delhi and its first Vice Chancellor. He was a renowned journalist as well as an Urdu poet.

The street was previously known as Pydownie Street thanks to a British perversion of the word 'Pydhonie', which literally translates as 'a place where feet are washed'. This probably was the first portion of the land permanently reclaimed from the sea.

The 'foot wash' area can be recognised as a small creek that formed during high tide between the islands of Mazgaon and Bombay.

|

| Mohammed Ali Road -Now |

The street, abuzz at all hours of the day, epitomises the spirit of the city that never sleeps. Being a primarily Muslim dominated area, it comes alive during in the period of Ramadan. Gastronomists throng its by-lanes that tempt all with offerings of mouth-watering delicacies. Famous sweetmeat shops like Zam Zam, Suleman Usman, Ghasita Ram, Hatim and Lookmanji flank the road.

Amidst the chaos, the light green coloured Minara Masjid sparkles under a cloud of tiny fairy lights during festive nights. Another one of the primary landmarks in the area is the Mumbadevi Temple that was financed by a goldsmith called Pandurang Shivaji Sonar.

Today, the JJ flyover (now renamed after the saint Makhdoom Ali Mahimi) curves above this street for 2.1 kilometres, making it the longest viaduct in the country.

Round Temple Sandhurst Road (Year unknown)

The Round Temple of Bombay is also known as the Gol Dewal and is located on Sandhurst Road in South Bombay. Around the temple is a 'stone' market said to be the city's oldest; here, one can choose from a wide variety of stones to use to furnish one's home.

|

| Round Temple - sandhurst Road - Then |

Sandhurst Road is also a railway station on the Central Line of the Mumbai Suburban Railway. The area is named after Lord Sandhurst, who was the Governor of Bombay from 1895 to 1900. The station was built in 1910 using funds from the Bombay City Improvement Trust, which he had helped raise.

The Trust had been created in response to the plague epidemic of 1896 to improve sanitary and living conditions in the city.

|

| Round Temple - sandhurst Road - Now |

The railway station was built in 1921. The supporting pillars of the edifice bear the inscription "GIPR 1921 Lutha Iron Works, Glasgow". (GIPR stands for Great Indian Peninsula Railway, which was a predecessor of the Indian Central Railway.) The fabricated metal was imported from the United Kingdom

The Bombay Club (Year: 1845)

In the Fort area was a historical club founded by the members of the Indian Navy as far back as 1845. As suited them and their proud vessels, it was within a stone's throw of the dock and the harbour.

It was situated in Rampart Row, West, which has sometimes been called Ropewalk. It was located on the premises, which had been afterwards occupied for years by the P&O Company.

|

| Bombay Club - Then |

This Club, of course, was confined to members of the Indian and Royal Navy. It, too, had its own rich naval traditions, which seem to have been lost in oblivion, but one could wish that they were ransacked and collected in a readable form, as they would constitute a distinctive and remarkable chapter in the making of Bombay for a century.

In the 1850s, the Bombay Club, as it was called, was a flourishing institution; and though strangers were confined to the tearoom, the one proud trophy the Club possessed was to be seen there. It was a bell, which one of the warships of the Indian Navy had brought as a prize from the first Burmese War.

The bell is still in existence, having been taken over as a valuable historical asset from the old Club by its successor. The present Bombay Club is in no sense a naval club. It is open to all European merchants, specially bankers, traders, mercantile assistants and brokers. But the glory, which the Indian Navy shed on its own original institution, is gone.

Oriental Buildings and Hornby Road (Year: 1885)

One of the first few buildings to come up in the Fort area was the Oriental Building in 1885, which cost Rs 87,000 and initially housed the Cathedral School.

In 1893, the building was sold to the Oriental Life Assurance Company; and with the proceeds the present Senior School building, a beautiful blend of Gothic and Indian architecture, was erected and occupied in 1896.

|

| Oriental Building - Then |

Starting from Crawford Market, passing by Victoria Terminus and stretching all the way to Flora Fountain is the Hornby Road, now known as Dadabhai Naoroji Road. It was a simple street that was widened into an avenue in the 1860s, and is now studded with structures built in the Neo-Classical and Gothic Revival styles of the 19th century.

Besides the three mentioned heritage sites, the road also displays the grand structures of the Bombay Municipal Corporation, Times of India, JJ School of Art, J N Petit Public Library and Watcha Agiary.

|

| Oriental Building -Now |

The history of Hornby Road, named after the then governor William Hornby, can be traced to more than 200 years ago when the British East India Company built the Fort that was later demolished to make space for growing civic requirements. It was then that the small street was broadened into an avenue and impressive buildings built along its stretch.

These structures, built between 1885 and 1919, were constructed in accordance with mandatory (government regulation of 1896) pedestrian arcade in the ground floor that performed as the unifying element tying together the various building facades. The result was a splendid spectacle of structures in various architectural styles linked together by a continuous ground floor pedestrian arcade along the street-scape.